Introduction

This article is the second part of the topic of Defining Exercise. In this part, we will go through the most popular exercise programs and describe what purpose they all serve. As you will find out, only a small amount can be legitimately counted as Exercise, based on the previous post’s definition. This second part of our Defining Exercise post will give us the knowledge to understand why Exercise (for the benefits of health and longevity) requires a specific protocol and what the purpose of other activities mentioned is. After going through this post, we will know how to choose the right kind of activity based on our desired lifestyle goals and health outcomes.

So much activity, not much exercise

In today’s health and fitness environment, we can observe many different physical activities, most claiming to provide certain health benefits. Let’s list a few:

- Olympic lifting

- Weight lifting

- Cross-fit

- Calisthenics

- Pilates

- HIIT

- Sports

- Running

- Yoga

If we look closely, we see that it is hard to lump all of these activities into one concept called Exercise. Instances differ in their skill requirement, intensity, duration, etc. Specifically, based on the definition of Exercise provided in this post, only weight lifting could be potentially counted as Exercise, under the pretense that the execution follows the following rules:

- we are focused on internal cues of muscular fatigue,

- we are performing simple movement patterns requiring little coordination, and

- we are following the laws of biomechanics to avoid disadvantageous joint positions

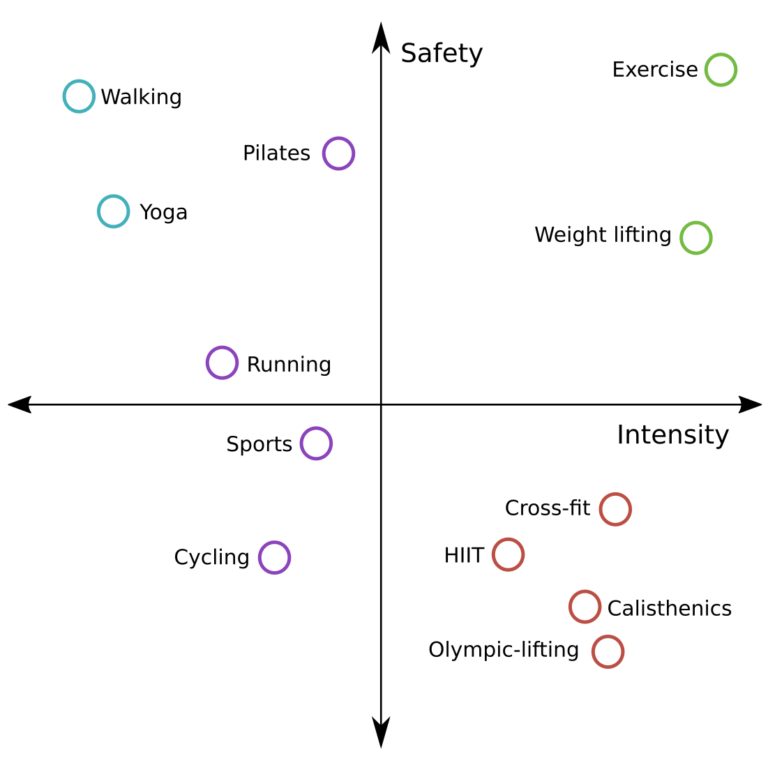

The main two distinctions between different physical activities are their intensity (which is inversely related to the duration) and skill requirement, i.e., safety. To distinguish between Exercise and non-exercise physical activity, we will place the before-mentioned activities into the Intensity-Safety quadrant.

Intensity - The main ingredient for improvements

While the definition of intensity is not strictly available yet, we will offer this one: Intensity is defined as the number or percentage of motor units (of the targeted muscle) being activated at a given time. Physical activities that allow the higher amount of motor units to be activated are of higher intensity than those that activate fewer.

Since measuring motor unit recruitment is hard without a special device, another measure of intensity is the rate at which the activity can fatigue the targeted muscle [1]. In practical terms, this means how efficiently we make the targeted muscle weaker. A physical activity that provides constant tension on the targeted muscle allows little to no rest while performing the movement and avoids disadvantageous joint angles and positions are most efficient [2]–[4].

Safety - The other ingredient providing longevity

On the other hand, safety is a measure of the probability that we get injured. The safest movements require little skill and proficiency to reach a deep level of muscular fatigue. Another sign of safety is the amount of practice time required to perform a particular movement pattern proficiently. Movements used for Exercise don’t require much learning time. Therefore, they can produce changes to our body earlier compared to more complex movements, where time is used for learning a particular movement.

The Intensity - Safety Quadrant

Based on reports on injury rates and each physical activity’s duration, we can plot a Intensity-Safety quadrant [5]–[9]. On the left side of the quadrant, the activities lack the required intensity to produce meaningful changes. On the lower part, the activities are prone to injuries. The most health and longevity promoting activities are those that can avoid injuries while providing a substantial level of intensity. Exercise presents the gold standard of safety to intensity ratio, as shown in the image below. Other activities deviate from that ideal. And the more deviation there is, the less appropriate these activities are to improve health and longevity.

Relaxation activities

Activities like yoga and cardio type activities (blue dots) are activities we can perform multiple times a week and even multiple times per day. The nature of such activities is of low impact and low-intensity movements with no added resistance. Thus, muscular and systemic fatigue is not increased, and there is little irritation on the joints and ligaments (in most cases).

While these activities will not produce much improvement in long-term health markers (strength and muscle size), they will bring forth other benefits. The most appreciated are relaxing tight muscles, increasing blood circulation (as a direct result of doing the activity or indirectly breaking up the previous monotonous activity), breaking up static body position, etc.

We add relaxation activities to our daily routine to balance out our time spent in a particular posture and relax overused and tight muscles.

Play activities and sports

Playing sports or participating in group activities like Pilates (purple dots) adds the element of fun to our physical lifestyle. Activities like that add enjoyment to physical movements, which is definitely a welcome thing for our daily experience.

Play activities can range from straightforward and safe activities like Pilates to technically challenging like many sports are. A typical session in a play activity can be of longer duration (multiple hours), which denotes that intensity is relatively low. Therefore, play activities are not suitable for improving muscular strength and size and should be counted as activities we do because we enjoy doing them.

A lot of play activities can be a source of many injuries, however. Often, the injury source is not the movement pattern of the activity but the dynamic environment in which the activity is being performed (cycling, swimming, playing basketball, etc.). Accordingly, the amount of play activities we perform weekly usually diminishes as we get older.

Resistance based sports

Now we are moving to the right side of our quadrant. On this side, we have very intense activities, which produce great benefits for improvement in muscular strength and size.

The first group (red dots) are resistance-based sports. Here, we count activities that require moving a certain resistance in a particular way—specifically, Olympic lifting, CrossFit, powerlifting, calisthenics, etc. With resistance-based sports, the main aim is an external goal – completing a lift or particular difficult movement, completing a certain amount of repetitions, enduring particular force, etc. Therefore the positive health-related outcomes of performing such activities are a side effect and not the end goal. For that reason, these activities suffer from a very high chance of injuries [5], [6].

While resistance based sports will undoubtedly produce positive adaptations to the muscular system, a high risk for injury is far from a desirable property. Adding complexity to a population where motor cognition and proprioception are not a strong suit increases the chances of injury. Exercise should not discriminate based on how crafty we are with our body and should allow anyone to get positive benefits as soon and directly as possible. Safety is, therefore, as important (if not more) in an exercise program as is intensity. Hence, we should avoid resistance-based sports until a proficient level of skill has been acquired, and the competitive part of the sport itself is something we would like to be enrolled in.

For best success in such endeavors, one should initially start with Exercise to build strength and eventually add skill-based training to become more proficient in the specific movements required for the sport. Aiming to improve one’s health with skill-based activities is a mistake.

Resistance training and Exercise

The last group of physical activities that we are left with is resistance training, where we differentiate between weight lifting and Exercise. Both types of activities aim to provide loads to challenge the musculoskeletal system, which will force it to adapt and improve.

The main difference between these two activities is that Exercise, by definition, emphasizes the movement biomechanics and the low skill requirement of a movement pattern. Weight lifting, on the other hand, doesn’t necessarily include that into its definition, even though including safety into weightlifting doesn’t negate its main purpose. Still, here we think of weight lifting as a collection of different approaches to loading muscles, where they can be more or less safe. We have many real-life examples of bodybuilders, for instance, where muscle growth has been achieved while provoking long term injuries.

On the other hand, exercise doesn’t allow for such a broader definition and accordingly doesn’t require much if any skills to be performed. By definition, exercise avoids injuries and improves our ability to move and perform daily tasks.

Conclusions

This blog post looked through the most common activity programs and placed them inside the Intensity-Safety quadrant. With this, we can differentiate between Exercise and non-exercise physical activities. This is important to avoid wasting time, effort, and prevent injuries. Doing so assures that the activity we choose to do serves the initial purpose or goal we set up. And specifically, at BrevisFit, we aim at improving your health and longevity.